B.W.O.

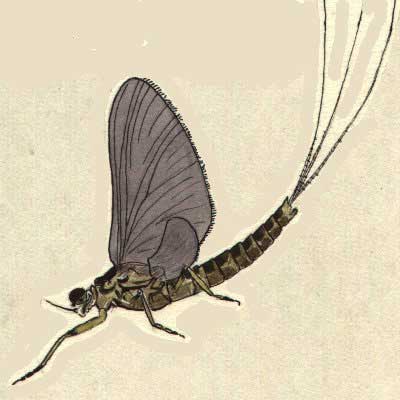

I

came to know this abbreviation for a dayfly very early in my career as a fly

fisher – just after 1950 I borrowed G.E.M. Skues’ book “The Way of a Trout with a Fly”. The name itself fascinated me

– it had a smell like the name of a vintage port or an old cognac. Its whole

name is Blue-winged Olive, and in latin Ephemerella ignita (ignita means fire or

flaming). It moreover enforced my interest in this dayfly that it was on the

main menu on my favourite stream Binderup creek through the whole summer.

I must admit that in spite of the fact that Skues mentions a special rise form

– the kidney shaped rise – to this insect, that I have never seen it, and as

my good friend, the late Oliver Kite once said to me:” I would get tears in my

eyes if I met a person who knew a person who had seen it!”.

Skues

has in his book “Nymph Fishing for Chalk Stream Trout” a pattern for the

B.W.O. nymph, no. XVIII.

| Hook: | No. 1 or 2 down-eyed round bend. |

| Tying silk:. | Hot orange. (Pearsall’s Gossamer No. 19). |

| Hackle: | Dark but definitely blue hen – as woolly in the fibre as can be had – two turns. |

| Tails: |

Thee strands of dark hen hackle - short. |

| Body: |

Cow-hair the colour of dried blood, dressed fat – the nymph itself being fat

and not taper like the other dun nymphs. |

This

special wool is mentioned in Skues’ “Side-Lines, Side-Lights and

Reflections” in the chapter

“ Occasionally it” But before Skues it has

been mentioned by another English author H.C. Cutcliffe in his book “The Art

of Trout Fishing in Rapid Streams”. 1863 page 56:

“….with

some bullock’s hair, of dark, almost purplish tint, which may be obtained by

searching along the palings in paddocks where bullocks are kept, and you will

find some little tufts appended to the numerous projecting points along the

rails, rubbed off and carded as it were by the animals scratching their sides

against the sharp points projecting from the timber…”.

I have myself collected this dubbing, when I as vet made tests for tuberculosis of cattle in the late winter, when the cows like all other animals are shedding their hair. It has no sense to try to cut the hair from cows or cattle - they are too stiff. Some of the old farmers did not allow their cattle to have their hair cut, when they were taken in-door in the autumn. I could find a few cows, where the black had turned into a dark purplish hue just before moulting. It could be removed rather easily in tufts and is of a soft texture. The reason for this change in colour can perhaps be the result of a lack of copper in their food!

My

stock of this special dubbing is now running short as a result of invasion by

fly tying friends; but I have found a solution: Black cows hair of the same

texture can get nearly the right colour if one bleach it with a strong solution

of hydrogen peroxide.

My

angling friend and I tried our efforts in making imitations of nymph as well as

dun.

I

only changed the tails on Skues’ nymph – I use the brown mottled feather

from a partridge, then the tails on the nymph is also mottled.

A

few years later I spend my vacation in a tent at Binderup creek together with

two of my sons – we lived for a whole week like boy scouts with fire etc. It

was in July and the B.W.O. was hatching each day like a metronome.

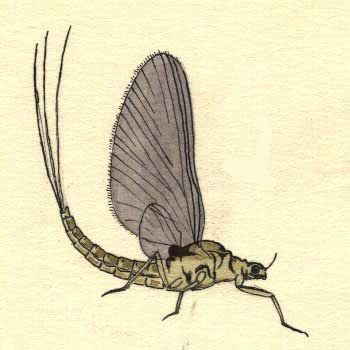

I

had brought with me paper and pen and moreover water colour paints. Beside that I

had from Oliver Kite got a field magnifying glass so that I could look at the

dayflies.

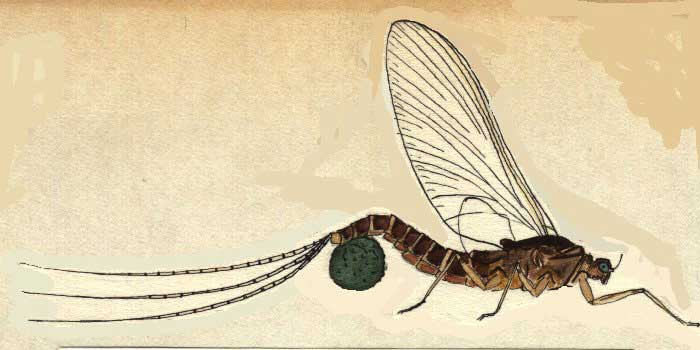

I

had in addition to confirm what J.W.Dunne had written in his book from 1924

“Sunshine and the Dry Fly” about the special act when the female spinners

end their lives on the steam surface – and I could confirm it!

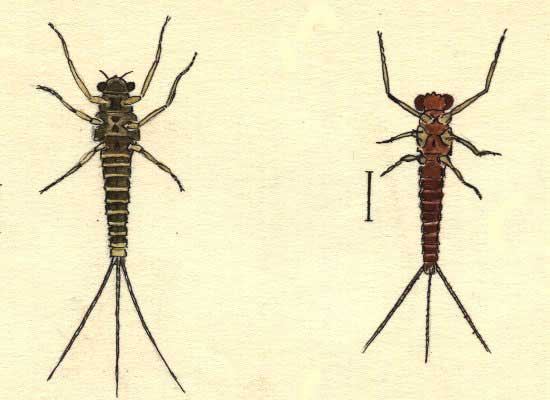

There

is also a big difference between the body of the male and female dun. One

can see it very clear looking up from underneath:

To the left:

B.W.O. subimago female - to the rightB.W.O. subimago male.

[A trustworthy friend of mine saw the other day at our stream a big sea-trout

jump out of the water to try to catch a swallow dipping on the surface...